Five key factors that determine organisational culture

From the beginning of time, human behaviour has remained very predictable. One of the most predictable aspects of human behaviour is that tension and conflict inevitably arise when two or more people are required to work together to achieve an outcome. That is a good thing. Tension and conflict are necessary conditions to achieve a heightened sense of purpose and when constructively harnessed, spectacular results are possible.

At an organisational level, culture is a factor of the interactions between the people in that workplace. Our collective ability to constructively manage workplace relationships, particularly in the face of inevitable tension and conflict, defines our organisational culture.

In the end, organisational culture has next to nothing to do with what type of work is performed, but how effectively we consciously and unconsciously resolve internal tension and the impact that this leaves on all involved. When managed well, the good will and trust that develops, positions an organisation and its people for greatness.

Therefore, when I am looking for clues to uncover what an organisation’s culture is really like, I am drawn to those things which are most likely to cause conflict in the organisation. Like a theatre production unfolding before you, if you sit back and watch how well or how clumsily, how aggressively or passively people manage organisational tension, then much will be revealed.

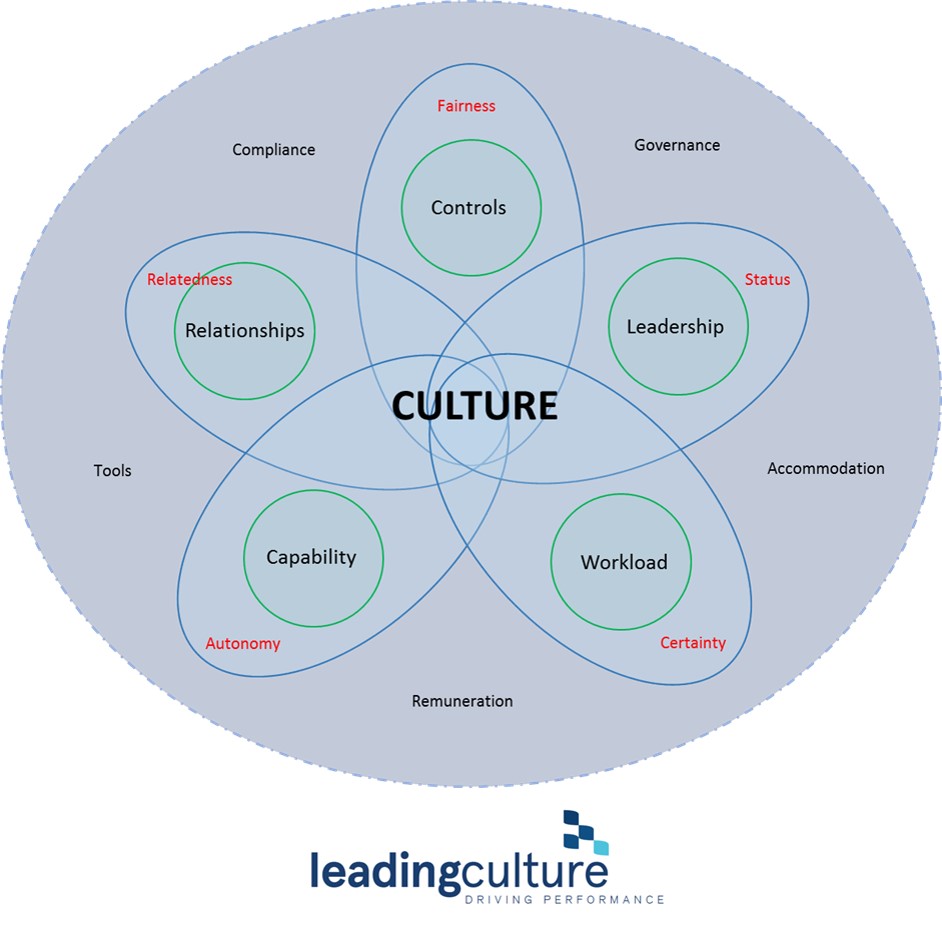

But what should you look for? After many years of trial and error, I settled on five main factors of organisational life that I try to observe and understand.

1. Leadership

How important is status in the organisation? How close or removed are top management from the shop floor? What gets rewarded and recognised by leaders? How do leaders communicate with their employees? How trusted are leaders?

2. Workload

To be clear, this is not an observation of the work itself, but of the expectations of how much of a load employees are expected to carry. Is the workload distribution equitable? Is it predictable? When an employee arrives for work today, will she know what lies ahead during the day? Is the workload shared and what happens to the work when they take leave?

3. Capability

How well are people trained to do their jobs? How long does it take for an employee to reach a level of job mastery? Is the approach to learning and to training structured so that employees can expect to reach a level where they can function in an autonomous way?

4. Relationships

Does the workplace support and encourage relationship building? What are the social norms of the workplace? What happens if somebody steps outside the social norms? Do employees trust the organisational complaint or grievance systems? How dependent are employees on one another in being able to achieve success?

5. Controls

What job controls exist to guide the work? How closely are people supervised? Is their work checked, approved or randomly sampled? Can an employee expect to receive regular feedback on their performance from a line supervisor?

These five categories are at the centre of the majority of organisational conflict. Interestingly, they align with the SCARF Model, developed by Dr David Rock, the pioneer of Neuroleadership. The five domains of the SCARF model are listed on the Leading Culture Model.

Invariably, there will be conflict around one of more of leadership, workload, capability, relationships or controls. At any time, there may be several people in the organisation who are in conflict around these factors. The manner in which employees are able to express their feelings of irritation and the desire and capability of the organisation to resolve issues in a way that demonstrates genuine concern and respect for the importance of these factors has a large bearing on determining its culture. Organisations that engage constructively and invest in each of these factors report far more productive cultures than those who do not.

Surrounding the Leading Culture Model are additional aspects of organisational life which are also relevant, but play a more static role in culture, rather than the dynamic role experienced by the five key factors. The tools, accommodation, remuneration, organisational governance and its commitment to adherence to legal compliance also play a significant contributory role, but only really become factors in influencing organisational culture when they are sub-optimal. To this end, I describe these as cultural hygiene factors.

Organisational culture is a complex issue. Leaders who develop mature work systems and model constructive behaviour around the five key factors will find that organisational culture becomes a much simpler issue to understand and master.